Books for the musician, music for the writer

My dad texted today. He’s received a package of books I mailed to him on Friday. He’s staying well through this pandemic: in high spirits and healthy.

Last year at this time he was stuck in the house with a string of illnesses that got in past immunity gates lowered by chemotherapy. I’m grateful that his greatest need this month, with the country halted and the public library closed, is books.

My dad, a professional musician, loves to read. It’s his main form of entertainment. As a child, he’d bring a stack of books home from the library and read his way through them in a week. This was during the period of his life, age 12 or 13, when his family invested in the medium grand piano that he still plays on today.

Practicing the piano was his work. Reading was his fun. The pattern is the same now. When he sits down at the piano or even turns on the stereo, he’s working. When he opens a book, usually sitting in the chair near his piano, with a small lamp next to it, he relaxes.

It’s the opposite for me. Books are work. Music is relaxation.

Read or play my flute: why do I have to decide?

At the end of a day of writing I play my flute to unwind.

I can’t get in the car without turning on music. Even the sounds of no radio—the thump of tires on pavement, the whoosh of other cars, the roar of nearby waterfalls, the calls of birds—turns into a kind of music I chill out to. When I was growing up, my dad never listened to music in the car. I struggled to understand. As soon as I learned to drive, I was blasting the stereo and seat dancing all the way.

But if I turn on the news, I’m thinking about how that story is structured. If I turn to Selected Shorts, that magnificent NPR show of out loud fiction readings, I often turn it off. There’s pressure there.

The same pressure exists with a book. I love to read, but never completely relax into a story. My mind jumps into questions of structure and voice. And also to my own work. Some of my most productive craft thinking goes on with a novel in the foreground. Perhaps the way a professional violinist draws inspiration from being in the audience during a symphony concert.

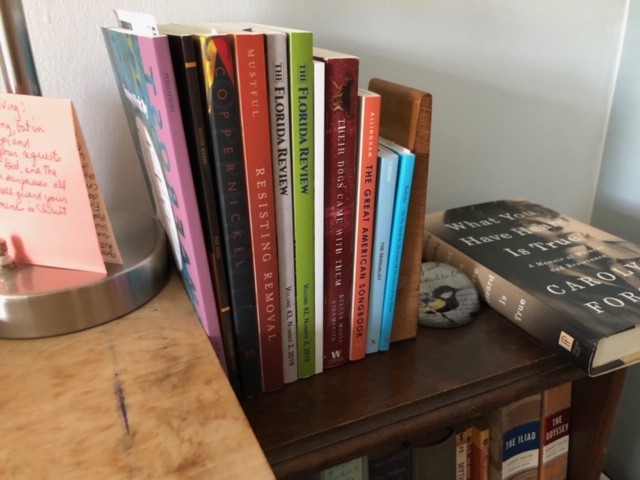

Books and journals wanting attention

This is a pity. Not only do I miss the entertainment offered by a book, I miss the book itself completely sometimes. My boyfriend, a gifted reader, puts me to shame by casually bringing up novels I should know, novels I’ve been tested on. Like last night, we were talking about the story I’m writing now, which has a narrative frame. “I love narrative frames,” Bill said, and proceeded to list a few: Catcher in the Rye, Wuthering Heights.

Wuthering Heights. I could barely recall the plot and main characters, let alone how the story was framed. As a novelist, I need to know this stuff. But my alert state around literature prevents me from sinking into a book, or a story or a poem, to a level where I truly know it and can therefore grow from it.

I want to learn to disappear as completely into a book, let it wrap me in some character’s life and carry me to another place and time, as my father does in his reading chair, his small lamp growing brighter and brighter as the sun goes down outside the west wall of glass.