All of life in one day; all lives in one novel?

I re-read “Mrs. Dalloway” with my friend Kelley, in our two-woman book group. The theme for 2021 is Distant Places; two travelers reading our way through the world when circumstances keep us at home.

Michael Cunningham wrote about Virginia Woolf’s “Mrs. Dalloway” in the New York Times late last year: “In ‘Mrs. Dalloway,’ Woolf insists that a single, outwardly ordinary day in the life of a woman named Clarissa Dalloway, an outwardly rather ordinary person, contains just about everything one needs to know about human life.”

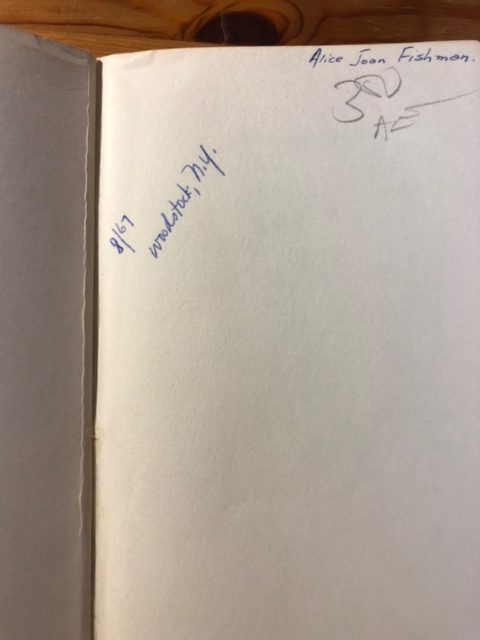

Really? In 2,000 years, when extraterrestrial explorers unearth and decipher my (rather nifty) 1953 thrift shop paperback copy of “Mrs. Dalloway” (inscribed “Alice Joan Fishman, 8/67, Woodstock, N.Y.”), will they suddenly understand human life?

Yes, Cunningham says that Woolf says, “in more or less the way nearly every cell contains the entirety of an organism’s DNA.”

I was skeptical. I decided to re-read.

The first time I read this novel of Woolf’s, my main concern had been to finish it in one day because—how clever!—the book takes place in one day. This second time through, I read more carefully, more consciously of the significant lives captured in that one day in June.

I read this time with a specific question in mind: Does a single day in the life Clarissa Dalloway really contain “just about everything one needs to know about human life?”

YES, the novel contains everything one needs to know about Clarissa Dalloway’s life.

From the moment Clarissa steps out to buy the flowers (“herself. For Lucy had her work cut out for her,”) to the moment she turns her attention to Peter at the end of the evening, we get a complete picture of who she is, where she lives, what she cares about, and why she savors life.

It’s the June day in London of a party she’s hosting, a day created to set her off like a jewel in a ring. But maybe any day in her life would tell me about her, if I were to drop into it.

She’s 50-something, the mom of a teenager, wife of a parliament representative. She savors life. She has intricate feelings about love. She’s aware of the passage of time—and is deeply disturbed by death as she is enraptured by life.

Clarissa and her loves, memories and experiences anchor the narrative, but the point of view, like a ghost, is restless, rubbing off to follow other characters around London at the slightest brush of proximity. the point of view dives into the woman who sells Clarissa the flowers, into her daughter, Elizabeth; into her husband, Richard; and intriguingly into Peter Walsh, the old lover of Clarissa’s whom she hasn’t, after all these years, forgotten. The Point of View Ghost dives mysteriously into Septimus Smith, a haunted WWI veteran and into his deleaguered immigrant wife.

Every consciousness was very full of things. “Mrs. Dalloway” is an urban book: densely populated in a way that reminds me of a walk along a crowed city street.

So what is universal about Mrs. Dalloway, both person and book?

- Consciousness is universal among humans; and each consciousness is universally unique.

- People don’t change, and each person has a lasting essence, much like the flowers Clarissa loves

- Time doesn’t stop. Big Ben chimes predictably—fatalistically?— as the hours pass.

And although we’re in London, the sea appears again and again. From the morning “fresh as if issued to children on a beach” to her memories of formative youth visits to the sea, to the moment—late at her party—when her old friend Peter sees her as a mermaid.

“Lolloping on the waves and braiding her tresses she seemed, having that gift still; to be; to exist…all with the most perfect ease and air of a creature floating in its element.”

I hear the rolling of the waves in the background of this novel as much as I hear London traffic. Water is universal, a shared resource and a common need. Consciousness is a stream one need only slip into to enter another similar and linked—yet unique—experience.

How does Woolf get into all those heads? In particular, I get the eerie feeling from Septimus Smith’s war-traumatized consciousness that the author really had been inside a mind like this; that a gifted writer can imagine her way into the true experience of someone who is not her.

This is a central concern of mine and always will be: if we can’t, as authors, imagine another person’s experience, then we’re each stuck writing only about our own lives. If we can’t as readers, then why pick up a book?

One of the reasons I love Mrs. Dalloway is that I am experiencing the world through many different points of view, primarily Clarissa’s, secondarily Peter’s and Septimus’. But also any person on the street or guest at the party. They are all worth lingering with and learning from.

“Woolf was among the first writers to understand,” Cunningham observes in the New York Times essay, “that there are no insignificant lives, only inadequate ways of looking at them.”

I’ve taken this on as a motto for my writing this year. I want to treat every character and her concerns and her very consciousness as deeply significant. Maybe not all in one day in one book, as the virtuosic Woolf does, but perhaps one at a time.