Read of the week: The point of view of the alien

In a lively text thread this week, three of my best writer friends and I discussed/debated point of view (the infamous POV) novel writing. I also thought a lot about a tweet thread on methods of keeping facts straight while writing long fiction.

Both conversations invigorated me, reminding me that there can be method to the madness of writing large-scale fiction. An organized brain with a plan just might enable a story to flourish. During a week when I’m struggling to revive a novel section by giving the antagonist a voice, these conversations about organizing POV gave me an “I can do this” feeling. Writing fiction is so much about imagining what someone else – some other POV – is perceiving.

So is science sometimes, it turns out.

I read in Wired this week a great article this week about point of view in space. Cornell astronomer Lisa Kaltenegger is looking out from Earth, wondering what the aliens see.

In a recent paper in Nature, Kaltenegger published a list of planets that – if they do harbor intelligent life – could be in a position to detect our planet by seeing Earth’s shadow “transit” across the face of the sun. The list includes more than 2,000 stars that might host alien worlds, and which are, will be, or would have been in the correct orientation in space to view Earth going back 5,000 years, and 5,000 years into the future.

Her research catalogues the clock of celestial bodies, turning the point of view back toward Earth: how might THEY find us, and what might we look like to them?

“This is how aliens might search for human life,” Kaltenegger says in the piece.

In the Wired article, Katrina Miller reports elegantly on Kaltenegger’s research – and on the whole idea of applying science to track an idea that’s previously been relegated to fiction.

“It’s a lovely piece of scientific poetry, to think about the way all of these objects are moving through space in this elaborate ballet,” says Bruce Macintosh, an astronomer at Stanford University who was not involved in the work.

Scientific poetry: I admire both Kaltenegger’s technical training, that enables her to line these facts up, and the imagination that inspires her to search for intelligent life in the universe.

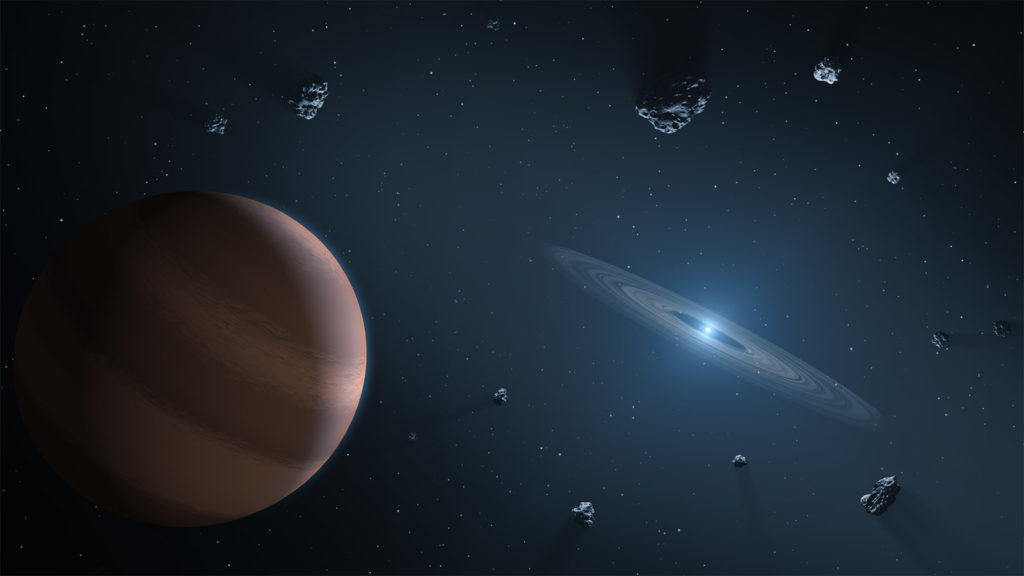

I reported on another of Kaltenegger’s papers last year, in which she details the possibility of life existing on planets orbiting white dwarfs – stars which have died.

“What if the death of the star is not the end for life?” she said. “Could life go on, even once our sun has died? Signs of life on planets orbiting white dwarfs would not only show the incredible tenacity of life, but perhaps also a glimpse into our future.”

Lisa Kaltenegger is a great example of how science needs imagination, the way imagination sometimes needs a little science.