Closet musician

The guy upstairs plays jazz piano. Of all the neighborly communications we get from him (water through pipes, heavy footsteps or, once, a smoke alarm followed by frantic running and the smell of burning dinner) I like his scales the best.

He is dedicated to exercises and plays only in the evening. Often, our dinner is accompanied by meticulous arpeggios or a chord exercise that is so pretty it sounds like a song, or the baseline of some piece I don’t recognize until fifteen minutes later, when he adds some layers.

He rarely misses a note. And even though it’s practice, it’s pleasant to listen to, made more beautiful by the fact that his pleasure in playing is not tied to anyone’s reaction.

Caroline Manring calls it “Doing a Thing.” Actually, it’s her nanny who coined the phrase, but Caroline uses it to describe the art and love she packs into her twins’ school lunches: “As long as my pleasure doesn’t hinge on a specific reaction from my kids (and yes the metric tons of lunch-begotten compost have assisted me in this slow but necessary letting-go),” she writes, “I say onward, dear little packet-packer.”

As long as my pleasure doesn’t hinge on a specific reaction from ______.

This sentence has traveled with me. I do so many things anticipating a specific reaction tied to them. Work assignments, certainly. Fiction writing sadly, as my inner editor chips away at the rough draft I’m crafting with unhelpful interjections like “no one will ever read this.”

Out for my daily run, the clock is watching me. Even family meal prep: I try not to take my 20-month-old’s food throwing personally, but some days I can’t help feeling that his dislike of scrambled eggs or tiny pizzas lovingly prepared is somehow my failure.

In “The Immortal Horizon,” Leslie Jamison explains that her brother Julian has completed five hundred-mile races because “He wants to run a hundred miles when no one knows he’s running, so that the desire to impress people, or the shame of quitting, won’t constitute his sources of motivation.”

What do I do when no one knows I’m doing it? When is my pleasure disconnected from anyone’s reaction?

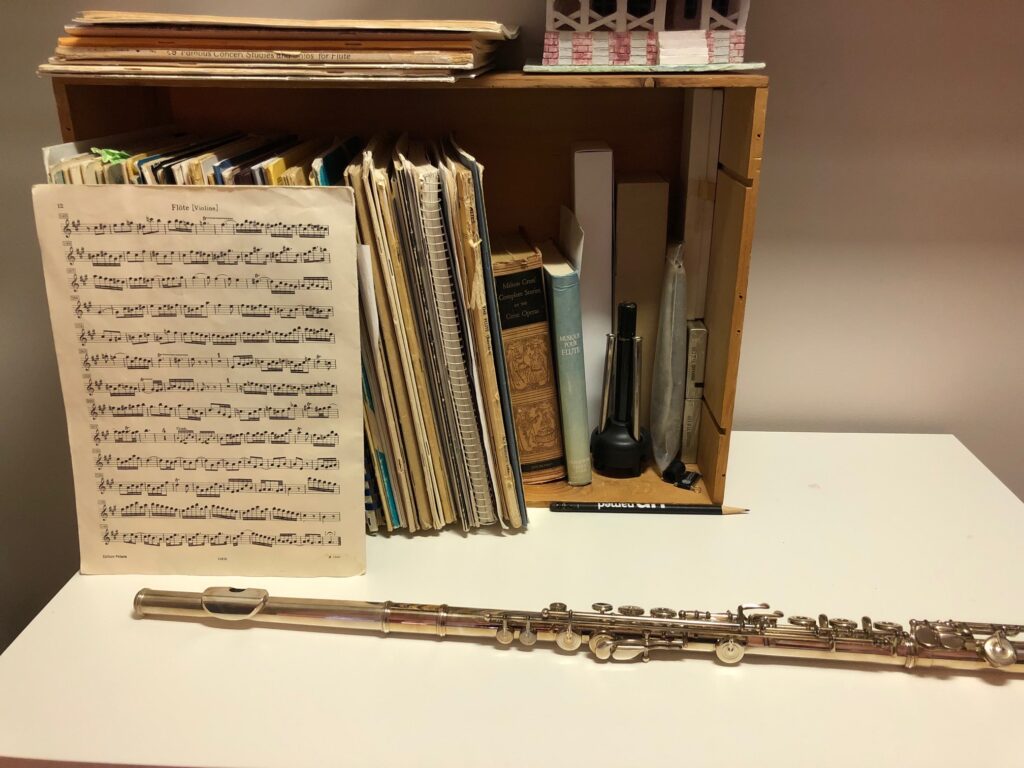

I play my flute in my closet.

Literally: my bureau fits into the closet in my home office, and it’s the perfect height to serve as a music stand, deep enough to host a crate of sheet music, and my flute case slides right into the top drawer. There’s even an overhead light.

And figuratively: I play almost every day, but when I’m alone (like when my husband is out running) so no one knows.

It frees me. The pressures of deadlines recede. The inner editor quiets. My brain takes a break from words and communication. Once in a while, the space between the music and my eyes and breath and hands vanishes so I can’t sense my own body and everything is just sound.

I have no idea how “good” it is, and I’m making an effort to not think about measuring up. For now, making music is enough and it’s just right.

If you’ve read this far, you now know that I play my flute in my closet, so it’s not a secret anymore. (The same way the many, many people who have read Leslie’s essay and watched the excellent film inspired by it now know that her brother runs ultramarathons unobserved.) But hopefully this will encourage you – especially those of you who, like me, are disproportionately motivated not by your own pleasure but by others’ reactions – to find that mental/emotional/artistic closet where you, too, can jam your heart out as if nobody’s listening. Because if they are, who cares?

I have no idea why my upstairs neighbor plays the piano. Most likely he’s an amateur who simply loves making music. Or maybe he’s a pro with a gig at a club in Boston and we just get to hear his scales. All I know is he’s not playing for us and I can hear the pleasure he takes in simply doing the thing. It’s a little contagious.